“Behind Enemy Lines,” Edward Wackowski (WWII-135)

By Virginia Hamrick, Intern

Listen: Oral history interview clip at UFDC with Edward Wackowski 00:43

Listen: Oral history interview clip at UFDC with Edward Wackowski 00:43

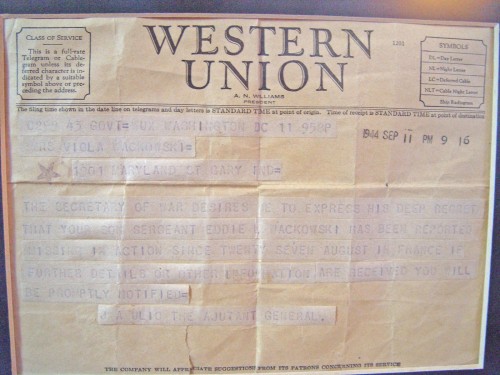

On September 11, 1944, Eddie Wackowski’s family heard he was lost somewhere in the European Theater. Though he was never captured as a prisoner of war, Wackowski experienced war behind enemy lines and recalled both his survival methods and also his fear.

Two years prior, Eddie Wackowski was drafted into the United States military. He grew up in Gary, Indiana, where he learned to fly at a nearby airfield. Because of his experience flying, he explained the military recommended that he join the Army Air Corps.

Once in England, Wackowski flew in several missions over Europe. Wackowski explained he served as an engineer on the plane: he oversaw the fuel levels and handled a fifty-caliber machine gun in case of a German attack. He also took pictures of the flight’s targets, explaining, “I had to get out there [in the open hatch] and lay down and take pictures where the bombs were falling.”

On his eighteenth mission, Wackowski’s plane was shot down by German forces over the French-Belgian border. The first French farmer Wackowski met offered him food and wine, but Wackowski, fearing Germans, insisted on hiding first. While hiding under a pile of wood, Wackowski heard Germans passing through the farm. After hearing the German soldiers leave, Wackowski and another soldier aboard the same plane fled the farm. The two soldiers sprinted through fields, getting caught on barbed wire, as they attempted to put as much distance between themselves and the crash sight as possible.

Not only did the threat of Germans worry Wackowski, but French forces also made him nervous. Wackowski explained the French Forces of Interior passed with guns “waiting to see if you were some kind of enemy.” The French Forces of Interior took Wackowski’s clothes, boots, and equipment, double checking each item was actually American.

Wackowski’s time in France revolved around hiding from German troops. Wackowski escaped from one home to another through tunnels. When German soldiers would come to homes asking for food, Wackowski hid in the basement. He was not the only thing being hidden — British forces would drop ammunition, and frightened French homeowners would store the weapons in the basements where Wackowski hid. He was surrounded by other frightened soldiers, anxious about being captured.

Wackowski eventually met an American lieutenant who took him to Paris so he could safely return to England. Wackowski mentioned German prisoners — on the plane to England, working refueling stations in the Canary Islands. Though he was never a prisoner himself, he was aware of the POWs on his return back to America. The treat of being a captured as a prisoner, and the subsequent anxiety, stayed with Wackowski throughout his service.

World War II veterans in both the Atlantic and Pacific Theaters were at risk of being captured as prisoners of war. For missing soldiers, like Eddie Wackowski, the risk increased as they tried to survive in enemy territories. As the risk increased, fear also grew. Anxious, Wackowski and other soldiers ran and hid. He was more aware of German prisoners and other potential threats. The fear stayed with Wackowski and other missing soldiers.

Photos donated by Edward Wackowski to the Samuel Proctor Oral History Program. For additional information about these and other histories, contact SPOHP, call the offices at (352) 392-7168, and connect with us online today.