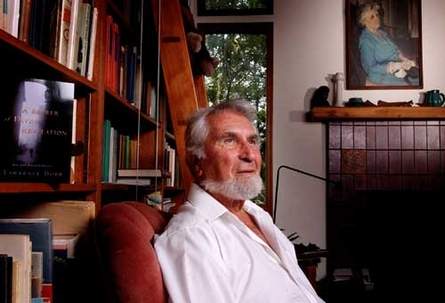

Janos Zsigmond Shoemyen, 93, died December 7, 2014, at his home in Alachua, FL. Shoemyen was a noted writer, nominated for the Pulitzer Prize in Fiction. He worked in the publications department of IFAS and taught Creative Writing for Santa Fe College’s Continuing Education Program for more than thirty years.

For a detailed biography of Janos Shoemyen, read “The words of a master,” by April Patten, The Gainesville Sun, July 25, 2004, and Shoemyen’s obituary, available online.

Remembrances of Janos Shoemyen

by Anna Muller, University of Michigan-Dearborn

Janos Shoemyen was interviewed by Anna Muller for the Samuel Proctor Oral History Program’s Authors and Literature collection in 2013, ALC-004. Thanks for Edit Nagy for contributing research and proofreading.

In the first ten minutes of my initial meeting with Janos Shomeyen, he mentioned his childhood and the tradition of putting boots outside on December 6, Saint Nicholas Day, in expectation of receiving a gift. I nodded in understanding. “You know that tradition? Of course you know that,” he answered his own question, agitated, and added jokingly, “you are civilized…” This joke established between me, a Polish speaker, and Janos Shomeyen, a Hungarian-born American poet an immediate familiarity. We are both from Eastern Europe, so these customs and traditions remind us of the rituals of our childhood. Janos, however, was not generally nostalgic for his past in Hungary. There were only moments, isolated images from his past, that brought back fond memories—absolutely “beautiful and real,” as he used to say—such as the visits of his maternal grandfather or Christmas celebrations. The rest of his story was buried in memories of wartime violence, Nazism, and Hungarian nationalism—“unreal,” as he called them—events and feelings that estranged him from the country of which he once felt a part.

Janos’s life narrative was built on contrasts: real and unreal, beautiful and horrible, intimacy and estrangement. As a Hungarian aristocrat he grew up speaking three different languages: he spoke French with his French mother, Hungarian with his Hungarian father, and German with his German nanny, with whom he and his sister spent most of their time. He began writing poetry in French when he was 12 years old, but it was the Hungarian language, nationalism, and politics that filled his early youth. As the son of a WWI war hero, he was destined to be in the military. In 1943, after attending the Ludovica Military Academy (the Hungarian West Point) for over a year, he joined the Hungarian army as a commander of the Third unit of the Second Panzer Division. They marched towards Kiev. When Janos narrated this part of this life, he spoke quietly and became almost incomprehensible. From time to time, I heard Janos use the term ‘unreal’ as a summation of his war experience.

Two years later, in the spring of 1945, the Red Army pushed back against the Hungarian advance. On April 1, 1945, Janos reached Sopron, a city on the Hungarian-Austrian border. The same day, the Red Army captured the city. Here, three days before the official liberation of Hungary, the war ended for Janos. Soon after, while still in his military uniform, he travelled to war-ravaged Budapest where he found his mother. His narration of his time in Hungary after the war ended was chaotic and incoherent. He became tired and agitated in the face of my repeated insistence on chronological order. There was a tension in his narrative, which perhaps reflected a desire to put behind him this chapter of his life, when daily existence resembled war: hunger, poverty, and an excessive reliance on the black market for survival. In the midst of the post-war chaos, Janos began working for the communist newspaper Új szó (New World). This phase of his life ended with his imprisonment for political reasons. Janos succeeded in escaping from prison, but this freedom meant leaving Hungary. After staying a short time in Vienna and Salzburg, in 1949 he decided to try his luck in England.

In England, he worked in a coal mine and began learning English, a language that sang for him. “It is not like putting tiles on the floor…” he said comparing it to German. “It is poetry…it sings.” When he met his future wife Clare, an American who was in England studying occupational therapy, he still barely spoke the language. In spite of their linguistic difficulties, he proposed during their second meeting. She laughed. Offended, Janos decided to leave England, but Clare stopped him by proposing to marry him. It was 1950. Within five years, thanks to the tutoring of Clare and her father, Janos began writing in English, and he wrote beautifully. English became for Janos the language of love, new life, a new way of expressing himself, and, after his move to the United States, the language of newly-found freedom. And yet, as I soon realized, he addressed his loved ones with diminutives he created by adding Hungarian suffixes to their English names.

What seemed to parallel this adaption of English was a growing estrangement from Hungary and Hungarian. He criticized Hungarian nationalism, the Hungarian aristocracy’s sense of entitlement and jingoism, and finally the post-war Hungarian history that enfolded in the shadow of communism. “This extreme nationalism makes you intolerant, you know…,” he often said. The presence of Edit Nagy, my Hungarian friend and colleague, during several of the interviews seemed to bring some of these feelings to the forefront. Having another Hungarian speaker in the room, he began to retrieve from his memory Hungarian terms that were more effective in describing the Hungarian reality of his past. These recollections, in turn, began bringing back more memories. For example, the Hungarian word raccsol—means a specific pronunciation of a letter ‘r’, different for the Hungarian aristocracy and the lower classes respectively. As a child and young teenager, Janos struggled with the correct pronunciation of certain Hungarian words in a way his class expected him to. He felt estranged from the class from which he originated, but due to these social origins, he did not fit into any other social group either. With time, as our interviews continued, his emphasis on the growing sense of alienation from everything Hungarian was becoming more pronounced.

From my first interview with Janos Shoemyen, I was trying to understand who he was. With a historian’s precision and a reliance on traditional historical documents, Edit and I tried to embed his individual story within a larger historical context. But nothing was straightforward in his biography, beginning with the two different birth dates that he used. He was a Hungarian aristocrat with deeply ambivalent feelings about Hungary’s past: on one hand, he had a deep nostalgia for the Hungarian hero and dictator Admiral Horthy, who collaborated with Hitler during the Second World War; on the other hand, he wholeheartedly rejected nationalism and the dismissive attitude of Hungary’s upper class towards those from the lower classes. He insisted that he had been confined in camps for political prisoners in Recks, but according to historical records, Recks operated between 1950 and 1953—a time when Janos was no longer in Hungary.

The details of his past, all the historical moments that we historians hold so dear, appeared blurred in his narrative. But he remembered people well. Their smiles. The impressions they made on him. The words he heard them speak. “He was absolutely beautiful,” he said about the first meeting with his English father-in-law. “Tall, a very English face… ‘I presume you are Janos’… I kissed him and he almost fainted. He was a priest and I confessed everything. And he said: alright my son, you don’t have to do that anymore.” While Janos remained reticent to fully share his past in the oral interviews, in his novels he explored it fully. And yet he denied it when I ask him if his novels represented his life. “My life is raw material,” he told me during one of our last meetings. “My stories are based on something, but then in the story, it becomes a different story and it is not me, ever…. It is fiction, but it is not.” Fiction “sings”, it helps us understand by pulling us into the story; it “sings” and thus becomes real. “Everything was fiction,” he insisted. His life and his stories became one, with blurred borders between what was real and what was not; with a blurred sense of what ‘real’ means for an individual—all this became his life, his own way of dealing with the difficult past, his own way of sharing it with others while maintaining his own secrets.

Janos’s life narrative was built on contrasts: real and unreal, beautiful and horrible, intimacy and estrangement. As a Hungarian aristocrat he grew up speaking three different languages: he spoke French with his French mother, Hungarian with his Hungarian father, and German with his German nanny, with whom he and his sister spent most of their time. He began writing poetry in French when he was 12 years old, but it was the Hungarian language, nationalism, and politics that filled his early youth.

-Anna Muller, writing about Janos Shoemyen

Photo by Doug Finger of the Gainesville Sun. To access this and other interviews, contact SPOHP, call the offices at (352) 392-7168, and connect with us online today.