by Génesis Lara, Latina/o Diaspora in the Americas Coordinator

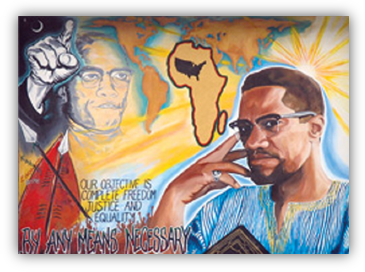

An introduction to the formation of the Latina/os Diaspora in the Americas Project at the Samuel Proctor Oral History program by Génesis Lara, including the preface to the Spanish edition Malcolm X’s autobiography by Juana Carrasco.

An introduction to the formation of the Latina/os Diaspora in the Americas Project at the Samuel Proctor Oral History program by Génesis Lara, including the preface to the Spanish edition Malcolm X’s autobiography by Juana Carrasco.

I spent my spring semester as a student in UF’s first study abroad trip to Cuba. Nine students, one professor, one life altering trip. I specifically remember my last day in Cuba. The sun was bright that day, just beginning to give off the heat that will soon have the Caribbean paralyzed. That last day of my trip, I was at the Plaza the Armas doing some last minute shopping with my classmates. As my friends looked through the stacks of revolutionary posters, I looked at the books that were on display. Weathered and frayed the books appeared like something you would find in an old treasure box. At least that is how I felt when I scooted down and found three books standing side by side. Each book was a Spanish translation of works written by the following authors: Angela Davis, Marcus Garvey and Malcolm X. There I stood, a hot summer’s day in Havana, Cuba holding a Spanish translation of Malcolm X’s autobiography.

Malcolm X’s Autobiography was the book that my friend and I decided to gift our professor as a birthday gift. That old and frayed edition, written in the 1961, found its way to the Samuel Proctor Oral History Program at the University of Florida as we began this process of launching the Latino History Program.

In this preface, Cuban author Juana Carrasco states that perhaps the greatest reason that the United States government feared Malcolm X was because he internationalized the Black struggle for liberty in the United States. To Juana when Malcolm said that the Black struggle in America, was the same struggle of the oppressed in Latin America, in Africa and Asia, that was when the United States realized that Malcolm X was a dangerous man. But why would that idea be dangerous?

If we filled a room at the University of Florida with people from the Hispanic-Latino community in Gainesville and we said to the audience “your struggle is part of a larger struggle” what would the reaction be? Some might say of course our struggles are connected to the outside world, don’t I send money to El Salvador every two weeks so that my children can eat? Another might say that he has not seen his wife and kids in years for fear of crossing the border again. A student might say, “I am Cuban and want to visit Cuba but my parents will not let me”. Another might say, “what does it matter? I have to work to provide for my family here.” And finally someone might say “Struggle what struggle? This is America, the land of opportunity”.

Then I thought about what if that same question was asked to a room filled with members of the African-American and Hispanic-Latino community in Gainesville. What would be the reaction then? How many would look across the room noting the similarities in appearance and wonder how and why? How many would look across the room wonder why the room is filled with people who look so incredibly tired? How many would see and choose not to see?

I do not think Malcolm had the answers for all these questions but I do believe he wanted us to ask these questions of each other. I think that is why his works were translated into so many languages. Malcolm wanted us to ask why each other hurts, why we are mad, why we are upset…he wanted us to ask why we are upset so that we can come together to find a solution. Malcolm said that we must learn to live together in justice and in love. He did not say how to do it just that we need to do it. I doubt that there is one clear cut answer, life rarely works that way. But I do believe that the first step in finding an answer is to listen to each other. We need to listen to our pains, our fears, our joys and our hearts. We need to listen, and we need to listen hard…only then will we come to know each other. Only then can we come to love one another like brothers and sisters, for we have been brothers and sisters for a very long time.

That is our hope with the Latino History Project at SPOHP. We hope to create a place where we can have these conversations, a place where we can begin to find answers to these questions, a place where we can do as Malcolm X asked of us: learn to live together in justice and in love.

–Génesis Lara, Spring 2014

Prologue to the Cuban Edition of Malcolm X’s Autobiography

“I do not expect to live the sufficient [time] to read my book” . . . he said one day, and effectively his prediction that he could be assassinated before his autobiography would be published was converted into a dramatic reality on the afternoon of the 21 of February of 1965, when he was beginning to address an auditorium filled with 400 Blacks and half a dozen whites.

“I do not expect to live the sufficient [time] to read my book” . . . he said one day, and effectively his prediction that he could be assassinated before his autobiography would be published was converted into a dramatic reality on the afternoon of the 21 of February of 1965, when he was beginning to address an auditorium filled with 400 Blacks and half a dozen whites.

Two men took advantage of the confusion created by their accomplices jumped from their first row seats inside the Audubon Hall theater and emptied their bullets at the body of Malcolm X, who for a few seconds stood erect in front of the bullets of his murderers, but all of a sudden falls to the floor – already mortally wounded – meanwhile one of the criminals emptied his gun in his body.

Betty Shabbaz, the wife of Malcolm X, and her four small children were present in Audubon Hall. Betty ran towards the podium screaming: “They are assassinating my husband! They are assassinating my husband!”

At 3:45 in the afternoon, in the Columbia Presbyterian Medical Center, the following news bulletin was given: “the person that you all know by Malcolm X is dead.”

The reaction of white North-Americans, headed by the press, was to identify the murderers and the motives of the murder with bitter vengeance of other black groups, the Black Muslims, the organization which Malcolm had separated himself from in early 1964.

Nevertheless, the reaction in the black ghettos and within the closest followers of Malcolm X is very different. Little by little, the consensus was reached that powerful forces, including the Department of State and the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA), were involved in the murder, because they were alarmed by the growing impact of Malcolm X, and particularly by his efforts to internationalize the problem of racial discrimination in the United States, attempting to bring the problem to the breast of the Committee for Human Rights of the United Nations through the diplomats of African countries.

With rigged declarations from false or bought witnesses, a trial was mounted against two members of the black nationalist organization of the Black Muslims; they pretended to demonstrate that the assassination had been a question “between blacks,” and the interviews and investigations that should have been realized concerning the actions and incidents that occurred never happened.

Because, in reality, situations were presented that clearly demonstrated that the Muslims could not have created the actions against Malcolm X that had occurred: interfering and recording all their telephone calls, following them across their trips to Europe, Africa and the Middle East, to cite a few.

A piece of evidence that was known years after helps to demonstrate that it was orders from the United States government that the murderers were following. Gene Roberts, one of the men that was supposed to protect the life of Malcolm, that formed part of his security detail in Audubon Hall, is one of the members of BOSS (Bureau of Special Services) organism formed by highly secretive agents of the police. Since Abril 4, 1964 he had infiltrated de OAAU, the organization founded by Malcolm X.

Malcolm X was assassinated when Gene Roberts was supposedly guarding him. And the majority of the members of the OAAU are imprisoned or dead. Gene Roberts later infiltrated another black nationalist organization, the Revolutionary Action Movement, and in a group known as the Mau Mau, and as culmination as his career as an agent within the most radical black organizations, in July of 1968 he infiltrated the Harlem Branch of the Black Panther Party. His testimony and his provocative actions served to incarcerate 21 Black Panthers in New York City, who were in danger of being condemned to strong prison sentences accused of conspiracy to rob various stores in the great city. Gene Roberts was finally unmasked in 1970.

One day, it will be known what was the exact role he played in the assassination of Malcom X.

The happenings that were occurring in 1965 demonstrated that Malcolm X was right when he told his wife Betty his belief that the North-American power structure was after his life.

That is why the New York Times wrote in December of 1965, “the majority of the admirers of Malcolm X begin to believe that he was assassinated by orders of the United States government.”

Malcolm Little, because that was the last name that he obtained from his parents on May 19, 1925, the day that he was born in Omaha, Nebraska, which was later converted into one of the greatest cities of the north. In the ghettos where he lived the great majority of his life since he was 15 years old, [he] was a thief, a drug addict, a professional player, a pimp. It is to say, he descended from the lowest point on the scale of humanity, to from there later transform himself into the most dynamic leader of the Black revolution in the United States. His example is compelling, and from there springs its danger.

“I have dedicated all the time that has been possible to me to this book, because I believe and I hope that if I tell my life story honorably and fully, it could convert itself, to the objective reader, as a testimony of social valor.”

“I hope and believe that the objective reader, in reading my life – the life of black man formed by the ghetto – can form a clearer image and a conscience of the black ghettos that are molding the lives of the twenty-two million Blacks that live in the United States.”

Now, in all the world, he is known as Malcolm X, the name that he acquired when in 1952 he left the prison in Charlestown and became a Black Muslim. And, in this organization of black nationalists, he is revealed as a genius orator that gathers thousands of new followers to the organization. But, at the same time, he is being transformed into a symbol of liberty and independence to the blacks of the ghettos. Continuing in the process of political awareness which is definitively what drew him to the religion of the Black Muslims, Malcolm X explores the oppression and discrimination of his black brothers and in 1963 begins to doubt the movement that he advocates for. Differences, clearly political, lead him to break with this organization on the 12 of March 1964.

Through his autobiography, dictated to the black journalist Alex Haley, he demonstrates himself in the image of the stereotypical black man assimilated by white culture until he reaches prison, and because of the doctrine of Islam is transformed into a sensitive man, proud of his black skin, of his curly hair, he identifies with his African origin and with the pain of his people, he politicizes himself and joins in the thoughts of the revolutionary and in conclusion, he becomes a MAN.

“I suppose that it would be practically impossible to find a black person in whatever part of the United States that has lived more deeply sunk in the mud of human society than me; or a black man that has been more ignorant in his life than I. That is why it is only after the most profound darkness when the greatest joy can arise; only after slavery and prison is when the sweet recognition of liberty can come”.

To comprehend the crises of identity, alienation, sentiments of hostility, discrimination, solitude, in which the black North American finds himself, and the reason of his struggle, an individual must read the autobiography and the writings and the speeches of Malcolm X.

“I gritted my teeth and held on with all of my strengths to the edge of the table. I felt that the comb was ripping my hair from my skull . . . how ridiculous I was! And how stupid that I reached ecstasies of admiration because my hair appeared like that of a white person . . . I had just finished, in reality, the first step towards my own degradation…I had entered the brotherhood of the black men and black women in the United States that are so brainwashed that they believe themselves “inferior” – and view whites as “superior” – until the point of violating and mutilating their own bodies.”

“I am not going to sit at your table and watch you eat, with nothing on my plate, and call myself a diner. Being here in America doesn’t make you American. Being born here in America doesn’t make you an American.”

These things that he said could not have been pleasant for the ears of many whites and of some blacks, but it was the truth about the situation of the community.

Controversial figure in life, the activists of the struggle for liberty of blacks now study his writings, his speeches, his autobiography, because the origin of the actual militancy active in the United States needs to be found in him. Afterwards, each one has interpreted him in their own way, but it is there, immovable and at the same time with a flexibility of the constant dialectic development that this revolutionary was submitted in, so that they have been taken advantage of and put to practice and enriched.

He gathered laughter and applause because not only did he say what the black masses had wanted to hear for a long time, but that he said it as one of the most brilliant and eloquent political orators of this era.

“I do not see any American dream. I see an American nightmare.” The bitterness, the hostility, the animosity of the racial intolerance of the white man in North America, all of this is manifested in his autobiography and his speeches. Also present are his last political ideas, the bases of his program of action for the Organization of Afro-North-American Unity, the organization that he founded, and these particularly motivated his assassination.

He plants the internationalization of the struggle of the black community in North America: “And if the twenty-two million black negroes see that our problem is the same as the problem of the peoples that are being oppressed in South Vietnam and in the Congo and in Latin America, then – then the oppressed of the land constitute a majority not a minority – then we can confront our problems as a majority that can demand and not like a minority that has to beg.”

Many have wanted to conceptualize Malcolm X as a black racist because he spoke of Black Nationalism. When Malcolm X spoke of the towns in Africa, Asia, and Latin America, he sometimes calls them black. With them, I want to symbolize the peoples who are exploited, but their position does not constitute an inverse racism: “It is incorrect to classify the revolt of the blacks as a simple racial conflict of the blacks against the whites or as a purely North-American problem. What we today contemplate is, better said, a global rebellion of the oppressed against the oppressors, of the exploited against the exploiters . . . the revolution of the blacks is not a racial revolution.”

And to highlight his sentiments that discrimination is a product of a system of social exploitation, he stresses: “All the countries that actually emerge from the claws of colonialism are currently turning to socialism. I do not think that it is accidental. The large part of the countries that were colonial powers were capitalist countries and the last stalwart of capitalism is actually the United States. For a white person it is impossible to believe in capitalism and not believe in racism. You cannot have capitalism without racism.”

The idea of valorization of the black person, as a man, as a human being, in the highest meaning of the word, and his international conception of the struggle of the black community in North-America, makes him be hated by imperialists; also his opposition and his denunciation of the war of aggression in Vietnam, the yanqui invasion of Santo Domingo and the envoy of mercenary troops to the Congo. But he is even more dangerous because he saw the importance of violence and with that he opened the eyes of the Black youth in North America. He exhaustively demonstrated what the revolutionary violence was able to accomplish in China, in Algeria, in Cuba, and what is being accomplished in Vietnam, and he therefore predicted the violence that would agitate the black ghettos in the United States and he advocated it [violence] as the necessary mean by which to reach liberty.

This edition that the Cuban Institute of the Book has made of his autobiography and fragments of his speeches allows us to understand that struggle of the Black North American community, symbolized in one of its most precise leaders, who with a direct language, simple, smooth, piercing and captivating – because in one sitting you can read and possibly reread this book – gives us a piece of history, a history that is still being written with blood and sweat of the Blacks and the exploited of North America.

–Juana Carrasco

For additional information, contact SPOHP, call the offices at (352) 392-7168, and connect with us online today.