By African American History Project Graduate Coordinator Randi Gill-Sadler

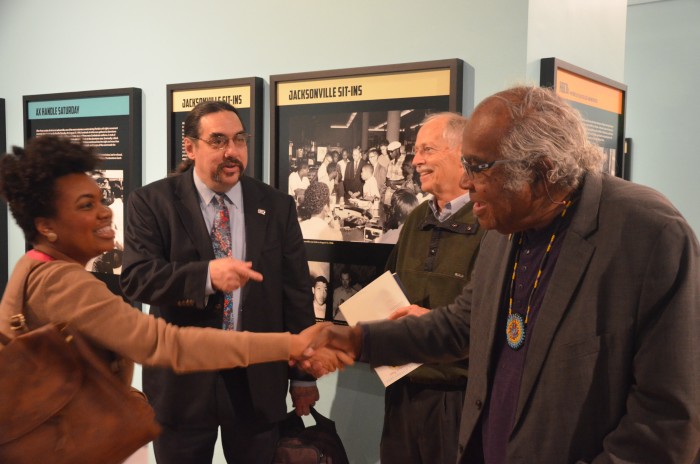

On February 27, 2015, as Black History Month was coming to a close and the eve of International Women’s History Month was approaching, Dr. Ortiz, several SPHOP coordinators and SPOHP’s official event photographer, Mr. Clayton, visited the “Civil Rights in the Sunshine State” Exhibit at the Museum of Florida History in Tallahassee.

- Check out SPOHP’s Facebook album gallery for more photos by Cornelius Clayton!

“This exhibit is the first of its kind to feature the Florida civil rights movement in such a prominent forum,” said senior research staff member Sarah Blanc. “It was executed thoughtfully, responsibly, and creatively.”

During our tour of the exhibit, we learned about the “wade-ins” to integrate beaches in Fort Lauderdale; we reminisced about interviews from the African American History Project that were featured in the exhibit. We even posed for pictures holding up our “V’s” alongside a picture of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. doing the same pose to celebrate the passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 in St. Augustine, Florida.

“It’s symbolically important that the exhibit opened in the downtown of our state’s capitol,” said graduate coordinator Jessica Taylor. “The recent interest in the civil rights movement here and across the state validates our own work, too.”

Civil Rights in the Sunshine State Exhibit Photos by Mr. Cornelius Clayton

Women in the Civil Rights Movement

The trip concluded with the Women in the Civil Rights Movement Panel. Chaired by Dr. Ortiz, the panel featured three extraordinary women: Dr. Gwendolyn Zohara Simmons, SNCC member, participant in Freedom Summer in Mississippi and UF professor; Sandra Parks, widow of Stetson Kennedy, participant in statewide Civil Rights movement and former city commissioner of St. Augustine; and Priscilla Stephens Kruize, founding member of Tallahassee CORE and leader in the Tallahassee Civil Rights Movement. Though each woman came from a unique background, highlighted by triumphs and trials alike, each HER-story shared that evening gave crucial and honest insights into the struggles and sacrifices that fighting for equality requires.

Recognizing Racism

Dr. Ortiz began the panel asking each woman about their earliest memories of racism. For Dr. Simmons, the warnings of her grandmother foreshadowed the racism that Dr. Simmons would oppose later in her life. “We were taught from a very early age not to engage with Whites because there was danger,” recalled Simmons. The murder of Emmett Till buttressed her grandmother’s warning. An avid reader of Jet magazine in the 1950s, Simmons remembered viewing the open casket photos of Till’s disfigured face in the pages of Jet in shock.

For Sandra Parks, racism’s effects on her life were not readily apparent. Parks’ grandfather was the head of the Florida School for the Deaf and the Blind. One day, Parks asked her grandfather why the white blind children couldn’t hold hands with the black blind children as they walked considering that neither group could see the other. Parks recalled his reply, “It’s not who they see; it’s about who sees them.” The irony of Parks’ grandfather’s answer was that Parks would be the one “blind” to the way racism was shaping the world around her and her Black nanny. Parks reminisced about her Black nanny, claiming that she spent more time with her than her own mother. But whenever she and her nanny went to the library; her nanny stayed outside, complaining that the library was too hot for her to sit in. Or when Sandra wanted to buy a soda from the local store, her nanny would complain that she was not paid to watch Sandra buy Coca-Cola from the store to avoid going. Parks admitted what she knows now that she didn’t know, or was “blind to,” back then: Her nanny could not go into the library or local store because she was Black. But instead of lamenting those circumstances to a young Sandra, she shielded her from the racist truths of the world around them.

Struggles Within The Struggle

Dr. Simmons and Priscilla Kruize spoke extensively on the external and internal obstacles to organizing, respectively. Dr. Simmons was admonished against joining the Civil Rights Movement by her family as well as her college. Before leaving home, Dr. Simmons’ grandmother warned her not to get involved in any of the “trouble” going on in Atlanta. College administrator echoed Simmons’ grandmother’s warning. Simmons recollected that the freshmen were threatened with the loss of their scholarships if they participated in the Civil Rights Movement—which was hard to avoid with SNCC (Student Non-Violent Coordinating Committee) headquarters two blocks away from campus and Ralph Abernathy preaching at a local church. Not wanting to lose her scholarship, as many of SNCC members already had, Simmons avoided joining SNCC and when she did join, only participated sporadically to avoid the putative consequences. But once Dr. Simmons saw her fellow SNCC members demonstrate such courage and boldness while being arrested for protesting, she knew she could no longer hide and fully participated in SNCC and in Freedom Summer Mississippi n 1964.

While Dr. Simmons came into consciousness via her membership in SNCC, Priscilla Stephens Kruize, along with her sister, Patricia Stephens Due, founded CORE (Congress on Racial Equality) in Tallahassee. Kruize and her sister had attended a workshop in Miami in 1959 and learned about CORE’s values and strategies including nonviolent protesting and testing an establishment before completing an actual demonstration. For Kruize, it was not external pressures that might have deterred her from the movement; on the contrary, Kruize expressed how she often doubted her ability to maintain CORE values, non-violence specifically. After recalling an incident where she was kicked in the stomach by a white man in broad daylight, Kruize discussed her own temptations to forgo nonviolent protest. “My thoughts were taking me to hell,” Kruize explained, “but I compromised and became nonviolent.”

Panel Photos by Mr. Cornelius Clayton

The Struggle Continues

The Struggle Continues

Each of these women are still active in the struggle for racial equality and social justice today. Despite living in a world where “post-racial society” rhetoric is gaining momentum and invites us all not to care about how racism still shapes our lives, each of these women articulated a commitment to continuing the struggles they began in the Civil Rights Movement and supporting the youth who are leading the charge in this new struggle. They all emphasized the current need for organizing, strategizing, and perhaps most importantly, love.

The panel, a tale of three female activists in many ways, further illustrated an important lesson that we all know yet never hurts to hear again: In the words of MLK Jr., “The time is always right to do what is right.”

-Randi Gill-Sadler

Photos by Cornelius Clayton.