by Aliya Miranda

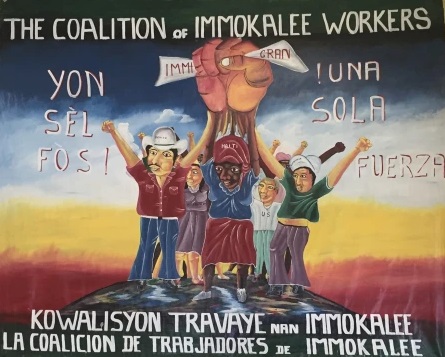

The first words Gerardo Reyes Chávez learned in English were, “Single file,” while on a 234-mile march from Fort Myers to Orlando in 2000. This was his first action as a part of the Coalition of Immokalee Workers (CIW), which has been advocating for worker-led programs committed to ensuring living wages, combating human-trafficking and combating gender-based violence for migrant workers since the 90’s. Since this march Gerardo has dedicated his life to representing tomato farmerworkers and improving working conditions for farmworkers everywhere.

Gerardo has been farming since he was eleven years old. Growing up in Zacatecas, Mexico, he was able to attend school until he was fourteen before working exclusively en el campo. Neither he nor anyone in his immediate family ever owned their own farmland in Zacatecas which placed the onus on him to find opportunities elsewhere. Gerardo knew at a young age that he wanted to start a family of his own, he wanted to have kids. He also knew that he would never subject those kids to the same lack of opportunities to pursue their own passions that he faced in childhood. He wanted to offer them a dignified life. He planned to move to the United States.

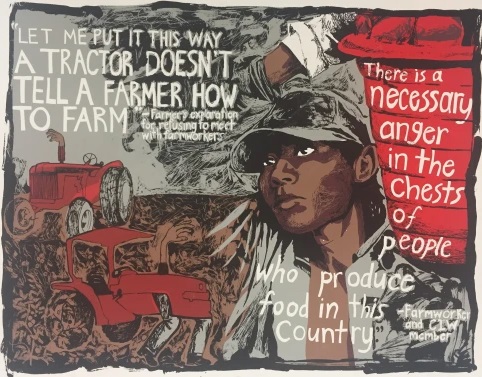

Gerardo recognizes Zacatecas wasn’t all bad. At the very least there were unspoken rules of honor between los campesinos y los patrones. For example, everyone had the right to take home some of the food they were harvesting without being questioned. If you brought home chilies, beans, corn, for yourself or your family, a good employer would encourage you to take whatever you needed. If an employer tried to stop you from taking a share home with you, word would quickly spread about this employer and it would inevitably ruin them. Farmerworkers had power.

Gerardo doesn’t know if it’s still that way today in Zacatecas, but he learned quickly that it was never that way in the United States upon arriving in Florida. Employer after employer he found no respect for farmworkers. One employer refused to pay him or his co-workers for their days of work, entrapping them in debt by selling them poorly cooked food while in the field before receiving their first paycheck. They stayed and worked for two weeks before fleeing. Without money, shelter or food they had to rely on the generosity of fellow farmworkers to get back on their feet. It was then that he came into contact and joined the fight for Fair Food with the Coalition of Immokalee Workers.

Gerardo joined the March for Dignity, Dialogue and a Fair Wage to the Florida Fruit and Vegetable Growers Association in Orlando after its leaders refused a meeting to discuss the concerns of farmworkers. On this march and many others thereafter he found an empowering sense of community and pride. However, his privilege of being a man without children who could afford to stop work to fight for advocacy without putting others close to him at risk does not escape him. He says in an unjust system where you have to decide between defending yourself or your children, programs like the Fair Food Program are essential for ensuring workers can advocate for themselves.

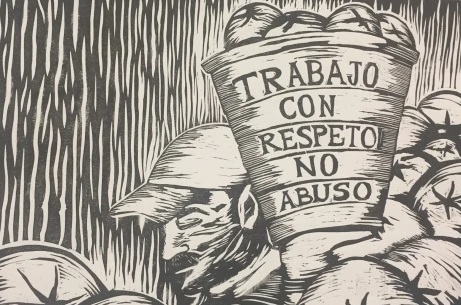

Under the Fair Food Program, the farmers are the monitors of their own treatment at work. Tomato growers, paid by corporations signed onto the Fair Food Program, are bound to comply with a strict code of conduct in the fields which includes protections from any kinds of threats of physical violence, sexual violence, harassment, or threats of termination of a worker for asserting the protections of the code of conduct. All farmworkers within the program are able to file complaints of violations of the code of conduct through a 24/7 toll-free complaint line which are then investigated by the Fair Food Standards Council. Participating corporations of the program are prohibited from purchasing food from growers in violation of the code of conduct which incentivizes compliance with these protections. These corporations are also required to pay a premium on top of the regular price they pay for tomatoes. That premium payment is then added as a line item bonus on the workers’ paychecks.

Through CIW’s campaigning they have been able to pressure corporations like McDonalds, Walmart, Aramark, Subway, Taco Bell, Whole Foods and many others to sign onto the Fair Food program. Since farmworkers organized for themselves Florida cases of forced labor, sexual harassment and wage theft are far more rare than they were before.

Concluding our interview, Gerardo had this to say about the futility of charity in effecting lasting change:

“…many people tend to respond to the needs of poor people in the only way that they have heard which is through charity, right? I try not to be judgmental and I’m not if the person is genuinely trying to help. Most people do that because they actually have a good heart, but the only thing they know to help others means to give away something to help that immediate need, which sometimes is desperate here if there’s a freeze that impacts the fields then people will be without a job for weeks and that’s necessary. If there’s a hurricane, same thing, people will be in desperate need, but as long as we do not ask why the need is there in the first place, as long as we don’t question it then it becomes a perpetual need…if everything was fair there would be no need.”

You can watch Gerardo give a Tedx Talk back in 2011 about his work with the CIW via the link below: