Occupations, Howard Lamar Long (WWII-200)

By Bruce Hunt, Intern

Howard Lamar Long, a veteran of the Second World War, was interviewed on the 2nd of April, 2012 and it was in that interview that he discussed, among other details of his service, his own account of living it Japan during the post-war occupation by America. He was trained as a medic and was meant to go to Japan on orders to treat the soldiers who were intended to be used in the proposed invasion in 1945.

When the idea of an invasion was abandoned and after the atomic bomb was dropped, he was moved to Nagoya in October 1945 and stayed there past the end of the war and was a witness to how the American GIs got on with the local Japanese population during the occupation. The relationship was antagonistic and involved near constant games of harassment in which Americans took advantage of the nation’s post-war poverty. As Mr. Long recalled, most Japanese at the time were suffering from tremendous poverty and many GIs took advantage of that vulnerability in order to feel a sense of justice for the soldiers they saw killed in the battles of the Pacific Theatre. This situation caused a moral conflict for Mr. Long and he has attempted to understand it in various ways since then.

The harassment of the Japanese citizens during the American occupation likely took a variety of contrived forms. In the interview with Mr. Long, he notes one specific method of harassment which he saw personally during his service. Certain American GIs would sell cigarettes to young and poor Japanese and then a second group might follow them and steal the cigarettes back to be sold to the next group of Japanese.

The GIs would get their cigarette allotment and they would sell it on one side of the compound.[…] to a, a Japanese and that Japanese would headed around going home, I guess, and the guys on the other side of the compound would take those cigarettes away from them. I never liked that.

-Howard Long (WWII-200)

To Mr. Long’s recollection, activities such as this did occur with some frequency throughout the duration of America’s occupation of Japan.

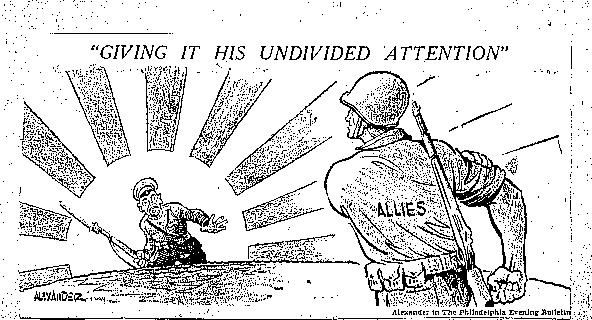

This political cartoon from an American newspaper shows how forcing Japan’s surrender was intended to be perceived by the public as an allied effort and not an exclusively American effort. If this was the case, then the occupation of Japan could also be made to appear like an allied effort as well, instead of American control.

Mr. Long himself did not participate in these activities but struggled to justify them even though he personally detested them. His job at this time was to count attendance at the meetings on the base and he stayed in Japan until January 1946. As a result, he remained on the periphery when it came to these instances of racial hatred.

These other guys, they were some that, you know, that hated the Japanese. Some of them probably had lost buddies and all this and I tried to rationalize it, but it was very difficult.

-Howard Long (WWII-200)

Mr. Long felt apprehensive toward condemning these men with whom he served because he understood they had a large amount of displaced anger they were dealing with. Still, he often noted that he objected vocally at the time and reinforced his outrage towards these activities during his interview.

After he returned home, Mr. Long attended seminary college and founded his own Baptist ministry in Kentucky, following the kind of moral conviction he had both before and after his service. However, it was conflicts like those mentioned here that still managed to prevent him from a complete and satisfying rationalization of his experience in the military. When he observed American GIs harassing Japanese civilians, he saw in action how anger and loss can reinforce culturally accepted racist beliefs. It was that realization which gave Mr. Long cause to reevaluate his own outlook on life both at the time and in incremental ways since then as well.

This piece of footage from the end of World War II shows how the American government expected the occupation of Japan to be perceived by the general public on the home front. From CriticalPast.com.

For additional information about these and other histories, contact SPOHP, call the offices at (352) 392-7168, and connect with us online today.