Of the many stories celebrating the accomplishments of military veterans appearing in today’s media, few are typically about women. Those women who served their country in the military during times of war are also grossly underrepresented in historical narratives, and therefore in the public consciousness. Women have played important roles in every war in which this country has fought, though they have often been overlooked. Early female pilots, nurses, medics, office workers, and many others took up jobs relieving men of duties, so these men could move closer to the battlefields. However, until the beginning of WWI, no branch of the American armed services officially permitted women to serve. Women in the Revolutionary War and the Civil War, for instance, had to do so surreptitiously, dressing as men or serving as volunteer nurses for injured troops.

Nathaniel Patch, author of “The Story of the Female Yeoman during the First World War,” details changes brought about by passage of the Naval Act of 1916 by stating, “On March 19, 1917, the Bureau of Navigation sent letters to the commanders of the naval districts informing them they could recruit women into the Naval Coast Defense Reserve to be “utilized as radio operators, stenographers, nurses, messengers, chauffeurs, etc. and in many other capacities in the industrial line.” The new enlisted women were able to become yeomen, electricians (radio operators), or any other ratings necessary to the naval district operations. The majority became yeomen and were designated as yeomen (F) for female yeomen… At the beginning, it was assumed the yeomen would perform only administrative duties, so the majority of the tests focused on office skills. In spite of the confining categories the Navy placed upon the yeomen (F), the women also worked as mechanics, truck drivers, cryptographers, telephone operators, and munitions makers.” (Prologue Magazine, 2006, para.8-10). Other women worked as translators, with some stationed as far away as Hawaii, Puerto Rico, the Panama Canal Zone, and Guam.

These women, the first to officially serve in the Naval Reserve Force (now Navy Reserve), soon became popularly known as “yeomanettes.” Because the U.S. Navy was not prepared to offer accommodations to them on naval bases, the women had to arrange for their own living situations. There were also no provision for uniforms, so the yeomanettes had to buy or make their attire by following the Naval Reserve’s general guidelines (no pants allowed). From the time the first woman, Lorette Prevectus Walsh, enlisted on March 21, 1917 until 1925, when laws were changed to exclude them, almost 12,000 served in the U.S. Naval Reserve (Homefront Heroines website). As historians and others have noted, “The successful integration of the Yeomanettes into the military served as a template when the Navy looked to ease a similar personnel crisis during World War II” (Hurd, Homefront Heroines website, para.3).

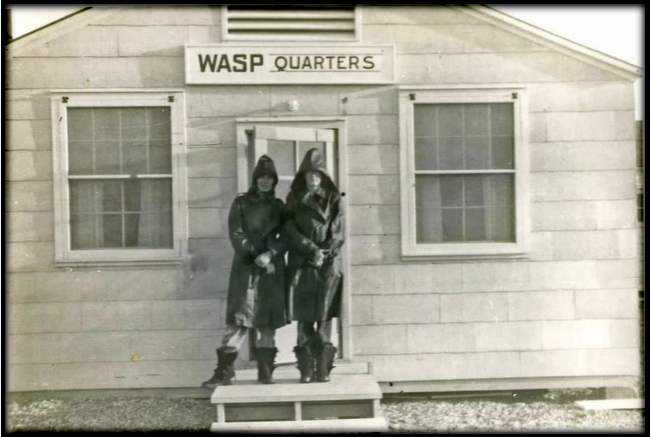

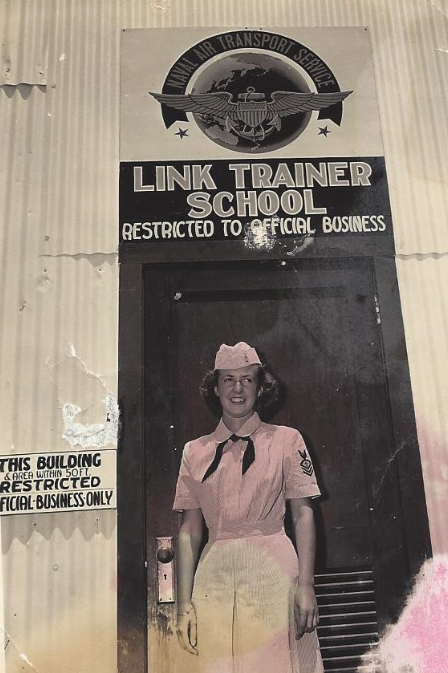

By the time Americans entered WWII in December 1941, not much had changed. Some women serving in the military had to make or modify their own uniforms, in addition to finding and paying for their own apartments. While men had their uniforms washed, pressed and returned, women fought for time to wash their own clothes and use the ironing board. Women’s barracks were inferior, with one woman describing their accommodations in the northeastern U.S. as located in an old brick building with broken windows. Since there was no security to keep out unauthorized males, she recalled seeing men’s boots outside her shower. Some female veterans, such as those serving in the Women Airforce Service Pilots (WASP) organization, were never given official status in the military and were designated as civilians instead. Female pilots contributed to American war efforts in a variety of ways. They flew disabled planes back from war zones for repair, as well as flying new planes from the factory to the air bases for the pilots’ flight training. From 1942 to 1944 WASP pilots flew 60 million miles and sustained 38 deaths and one MIA. WASPs were finally given veteran status in 1977, and were awarded the Congressional Gold Medal in 2009 for their WWII service.

Throughout the war, women worked in clerical typing reports and filing forms and in logistical positions working as drivers and support staff counting and distributing supplies, and performing many other jobs, in order to relieve able-bodied men for reassignment to areas where troops were needed. During WWII the shortage of able-bodied men opened up factory, shipyard, and munition manufacturing positions to women, who were able to learn new skills.

They were recruited through many avenues, including propagandistic newsreels. One of these films, entitled “Glamour Girls,” argued that “instead of cutting the lines of a dress, this woman cuts aircraft parts…They are taking to welding as if the rod were a needle and the metal a length of cloth to be sewn. After a short apprenticeship, this woman can operate a drill press just as easily as a juice extractor in her own kitchen. And a lathe will hold no more terrors for her than an electric washing machine.” (Field, The Woman Who Dreams Herself: A Guide for Awakening the Feminine, 2006, p.46.) Female riveters, who learned how to construct ships and planes in metal, have been memorialized in the iconic image of Rosie the Riveter, however there were many others working in more traditional professions. Military nurses cared for the wounded and sick on ships returning to the states for further care and treatment. The long voyages from Europe and the Pacific Fronts created challenges and rewards, sometimes leading to innovation in treatment.

In his master’s thesis on the experiences of female workers during WWII, Strohmetz concludes, “Although women were the beneficiaries of the new opportunities, this did not eliminate the limits imposed by their gender, race, ethnicity, class, age, and education. American women built the engines of war, rivet by rivet, and sacrificed their husbands, fathers, sons, and brothers, as well as themselves to the war effort. Victory only became a reality because of their shared sacrifices of time, sweat, and loved ones” (Women in Wartime Shipyards, 2017, p.9). Therefore, the veterans-related sources available at the Samuel Proctor Oral History Program includes the Home Front Project, which includes women whose roles supported war efforts.

When Samuel Proctor, a history professor who founded the collection at the University of Florida, began the collection with interviews from WWII veterans, and even an elderly Civil War widow, but not WWI veterans. As the collection has grown over more than half a century, interviews with women veterans have continued to document living conditions, work assignments, training issues, and other details from five past wars.

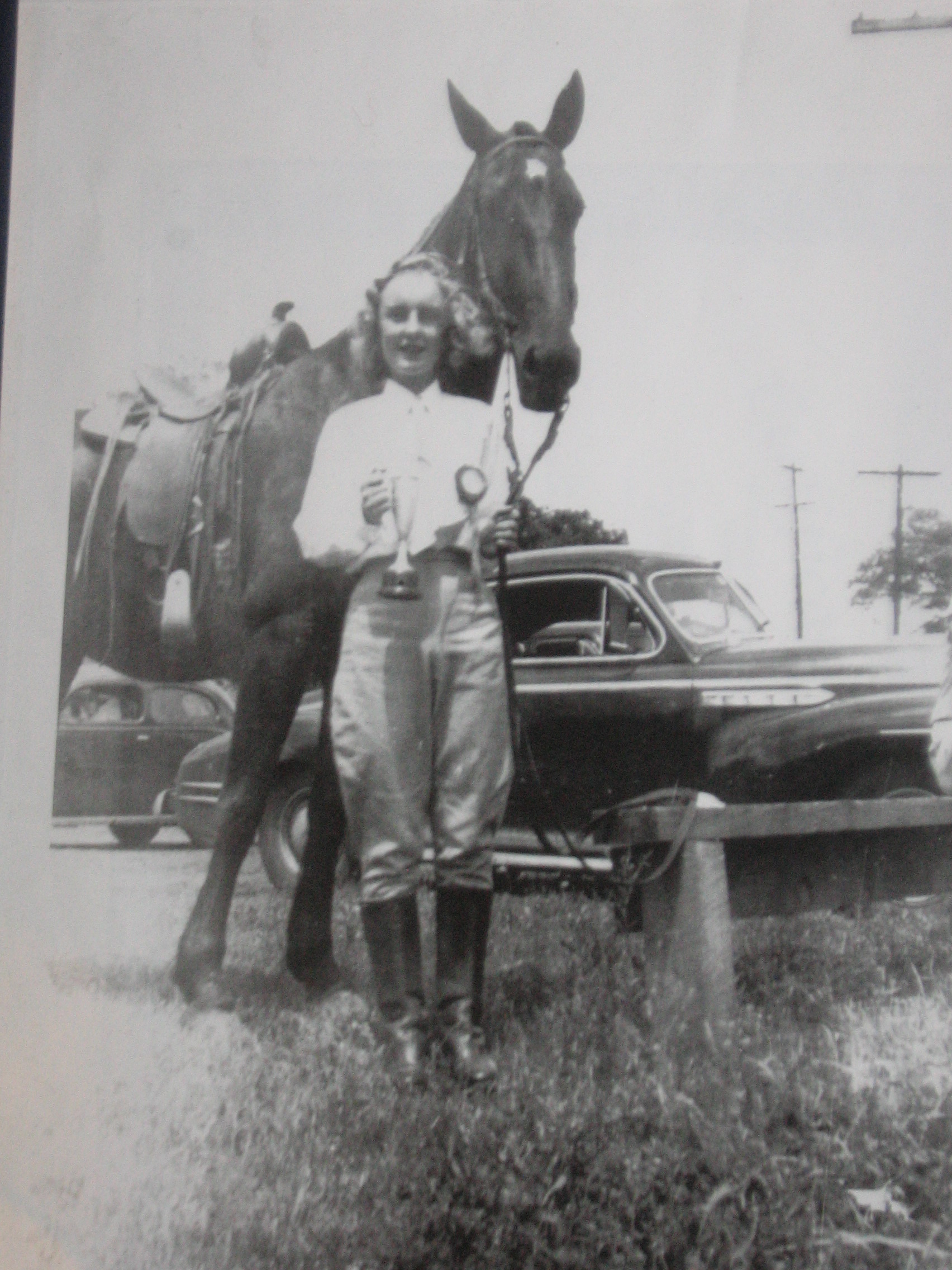

Though we have not collected as many interviews from women vets as we would like, their experiences cover a wide range of situations. For instance, Wuni Ryschkewitsch was a woman who was raised in Germany during the rise of Hitler. Her husband was a Russian military officer and, after they were safe in the U.S., raised a family. The title of her memoir is When Sex was Safe and Diving was Dangerous. In another interview, Constance Young’s daughter, Julia Nowlin, talks about her mother’s service as a pilot. Constance Young joined the service in 1942. SPOHP has material donated by Julia Nowlin on trailblazing aviatrix Jackie Cochran. Born in 1906 to a poor family in North Florida, she was the Director of Women Pilots, Headquarters Army Air Forces from June 1943 to December 1944, in charge of the all women pilot activities in the Army and the Women Airforce Service Pilots (WASP), and was the first woman to pilot a plane while breaking the sound barrier. Among the many military medals she received was the Distinguished Flying Cross with two oak clusters.

Many women served as nurses during more recent wars. During the Vietnam War, Linda Moody was an RN for a year. She treated very ill patients suffering from tropical diseases, such as three different types of Malaria, various strains of dysentery, and terrible infections in wounds of the feet due to poisoned pointed sticks placed in the jungle by the Vietcong. Other women, like Sue Dudley, the wife of an airman who served in the Vietnam War, have told vivid stories about her husband’s experiences and the effect of the war on her family. These stories and family photos are now archived as part of the associated Home Front Project.

Not all military service takes place during wartime or occurs in theaters of war. Christine Parker-Wheeler discussed her career in military intelligence assigned to service at the Pentagon, as a woman and non-commissioned officer (NGO), undoubtedly a rarity at the time. Her interview is listed under the general heading of Veterans History Project (VHP).

In the foreseeable future, SPOHP staff and volunteers will be working on collecting more interviews from women veterans, and on improving the cross-referencing with other SPOHP projects, such as AAHP or the African American History Project, which include interviews with women veterans. We will also continue to cooperate with the Library of Congress Veterans History Project (VHP). Please contact us if you know a veteran, who would like to contribute an oral history interview about her service experiences.

The following is a list of female veterans and other related interviews from the Samuel Proctor Oral History Program (SPOHP) archives:

World War II Women Veterans:

WWII 008 – Jane Reeves

WWII 009 – Vera Freifeld

WWII 034 – Julia Spach

WWII 042 – Margaret Lewis

WWII 050 – Anne Barbee

WWII 072 – Elma Decker

WWII 077 – Pauline Pepper

WWII 083 – Renee Fink

WWII 131 – Aurelia D. Wallace (“Chick”)

WWII 141 – Dot Whittle

WWII 142 – Julia Reynolds Nowlin

(veteran and daughter of Constance Young Reynolds,

who worked with Jackie Cochran as a WASP pilot)

WWII 153 – Clair Lewis Swarmer

WWII 166 – Ellen Sprow

WWII 171 – Wuni Ryschkewitsch

WWII 175 – Doris Lockward

WWII 176 – Elsebet Zafke

WWII 185 – Della Rosenberg

WWII 188 – Marion Freund

WWII 190 – Nakagawa-Iwata Margaret

WWII 197 – Frances Fronapple

WWII 201 – Alvina Bowen

WWII 204 – Ranata Spitzer

WWII 212 – Adelina Gerry

WWII 260 – Priscilla Getchell

WWII 263 – Dorothy Baggett

WWII 315 – Barbara Henegger

WWII 316 – Margaret Green-Witt

WWII 324 – Louella Salhanick

WWII 335 – Lucille Cooper

Korean War Women Veterans:

KW 011 – Maureen Eastwood

Vietnam War Women Veterans:

VWV 007 – Pam Morris

VWV 015 – Julie Netzer

VWV 018 – Danielle L. Truscio

VWV 041 – Nancy Tiger

VWV 048 – Mary Bahr

VWV 069 – Linda Moody

VWV 094 – Bonnie Gallegos

VWV 137 – Harbison & Pound

Gulf War Women Veterans:

GW 005 – Candy Lovett

Korean War Women Veterans:

KW 011 – Maureen Eastwood

AAHP 491 – Ernestine Dave

Women Veterans (not serving during wartime):

VHP 008 – Christine Parker-Wheeler

AAHP – Kenya McClain Ellis

AAHP – Dessie Robinson

Home Front Project- Women’s Contributions (though not veterans):

HFP – 001 Patricia Willis

HFP 002 – Nora Kent

HFP 003 – Mary Green

HFP 004 – Christina Marshall

HFP 005 – Sue Dudley

HFP 007 – Kay Anonymous

AAHP 180 – Alethia Viola Brown (welder at Norfolk Naval Shipyard)

SPOHP Interview with Ernestine Dave, a Korean War Veteran in Japan:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=SDMrg3R-95o (opens in new tab)

Women Veterans of the Persian Gulf War:

The Library of Congress Veterans History Project (VHP) commemorated Women’s History Month in 2012 with a panel discussion on the contributions of women to the Persian Gulf War and the impact on women veterans in the more than 20 years since. Panelists and veterans Darlene Iskra (opens in new tab), Julie Mock, Juanita Mullen (opens in new tab)and Gail Shillingford will share their experiences during the war and the impact of service on their lives. Lory Manning (opens in new tab), director of the Women in the Military Project for the Women’s Research & Education Institute, will moderate the discussion.

Video of Panel Discussion on Women Veterans of the Persian Gulf War, C-SPAN (opens in new tab)

Women Veterans of the Iraq and Afghanistan Wars:

Women veterans talked about their experiences serving in the Iraq and Afghanistan wars. The discussed their reasons for entering military service, dangers they encountered in war zones, skills used during their deployments, and their transitions from military to civilian life. “Women Warriors” was part of the New York Veteran History Series held at the New York Public Library in collaboration with Women Veterans and Families Network.