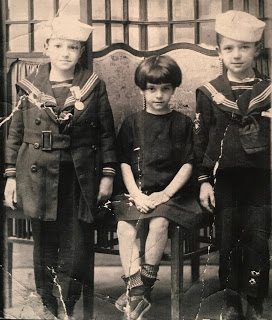

On September 13, 1922, a great fire erupted in the Armenian neighborhood of the city of Smyrna — modern Izmir — Turkey.[1] The city’s inhabitants fled their homes in a panic and made their way to the city’s quay. There they awaited passage out of the city without any guarantee of its arrival. The stories of those individuals are rarely the center of attention. This essay focuses on one such story which is also exemplary of transnationalism in a time of social collapse. It features the experiences of two sisters one of whom was named Cleo.[2] After petitioning US Consul George Horton, Cleo, her sister, and her three children were provided a full US Naval officer escort from their home to the quay of Smyrna. There they stood, awaiting passage with Cleo’s two boys, Kosta and Angelo dressed in sailor-style outfits.

Thirteen years earlier, an entrepreneurial twenty-nine-year-old named Anastasios left Smyrna for Charleston, South Carolina. He had just married Cleo and left her, and their three children – all of whom were from their first marriages – with her family in Smyrna. He worked as a barber in Charleston for 2 years and saved enough to return to Smyrna for her and their children. They returned to Charleston in 1911. By 1917, Anastasios established his own barber shop with the funds he accumulated.

During the same time, in the heartland of Asia Minor, Greek and Turkish armies stood across each other. The Greek army’s offensive against the Provisional Turkish government’s positions in the summer of 1921 resulted in a stalemate and allied interest in the struggle faded. In August 1922, what turned out to be the final clash between Greeks and Turks resulted in Turkish victory. The Greek army was sent into a disorganized retreat that culminated with their return to Greece from Smyrna on September 13, 1922.

Panic spread in the hearts of Smyrna’s residents when they learned the news of the defeat. At this point, nothing stood between the city’s inhabitants and the Turkish Army. That is when Cleo petitioned US Consul Horton and a few days later she stood at the quay with her sister and children. They stood in front of a dinghy with an American destroyer waiting for them off-shore. As Cleo and her party moved towards the vessel, the Naval officer in charge asked them to produce identification papers. Cleo presented her and her children’s naturalization documents but her sister was not a US citizen. The US Naval officer informed Cleo that her sister would have to remain on Smyrna’s shore.

In total shock, Cleo pleaded with the officer not to carry out this order, but to no avail. Cleo looked at her children, and then looked at her sister. The choice for Cleo was self-evident. She requested that the Naval officer return her, her sister, and her children back to their home. As soon as they returned, Cleo worked quickly to find passage out of the city. That night she paid for a barge to transfer everyone safely to the island of Lesbos. No one was left behind. The Greek and Armenian quarters of Smyrna were burned to the ground over the next five days. Horrific scenes of absolute destruction ensued. The surviving Greeks and Armenians landed as refugees in different Greek ports and lived in temporary refugee camps.

Cleo’s story is exemplary of themes of transnationalism and the role that citizenship plays in a time of social collapse.[3] Cleo kept her kinship network open while in Charleston and under unfortunate circumstances returned to her family in Izmir. Her US citizenship transformed into a major obstacle and negatively impacted her family. Cleo’s experience reminds us that legality – of citizenship in her case – and morality do not always coincide.

[1] Michael Llewellyn Smith, Ionian Vision: Greece in Asia Minor, 1919-1922: With a New Introduction (London: Hurst, 2009), 309.

[2] All information regarding Cleo originates from the following interview: Respondent Number 23, Interviewed by George Topalidis. Ottoman Greeks of the United States Project Archive, April 2015.

[3] N.L. Green, “The Trials of Transnationalism: It’s Not as Easy as It Looks”. Journal of Modern History. 2017. 89 (4): 854.