The displacement of Syrian refugees to European shores over the past five years has led US public opinion to revisit themes from the academic discourse about immigration. Isolationism, nativism, and restrictionism permeate modern public opinion and in the process transport its audience through a time warp to the early-twentieth century. These themes reverberate in the rhetoric of contemporary US public figures. They dehumanize refugees and thereby facilitate future immigration restrictions against them.

A hundred years ago, this type of public rhetoric resulted in the drafting of the most restrictive immigration legislation in US history: the Immigration Restriction Act of 1921. The act’s main provision established quotas based on a three percent immigrant admission rate per annum, itself derived from the 1910 US Census figures of each US resident’s country of origin.[1] When exhausted in a given year, the quotas restricted immigration and enacted the contemporaneous deportation procedure. This provision expanded immigrant categories of the 1917 Immigration Restriction Act.[2]

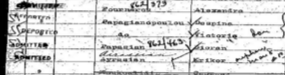

The aim of this essay is to raise public awareness about effects that such legislation had on some of the weakest targets of the time, ninety refugees from Smyrna. Port agencies and their staff were the first forms of officialdom that the refugees encountered. The state’s vetting system generated ship manifests, which recorded their arrival, screening, admission, quarantine, or in this case deportation procedures. Border agents labeled cases of deportation on ship manifests by applying a “Deported” stamp next to the names of the deportees.

“Deported”

The ship manifest of the S.S. Acropolis problematized the Smyrna refugees’ story as conveyed by contemporary press reports. The first issue contested was the actual number of refugees from Smyrna. Here, the newspaper articles provided nebulous and contradictory information. The first report by the New York Times cited ninety refugees with transitory immigration status. A month later, follow-up reports decreased that initial number to seventy, comprising fifty-one Armenian and nineteen Greeks. The Greek-American press contradicted that figure by noting ninety “primarily” Armenian refugees; without enumerating the Greeks.[3]

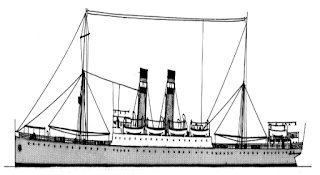

The SS Acropolis

The Ellis Island manifests provide an even lower number: a total of forty-four passengers from the S.S. Acropolis were deported.[4] Of those, eleven were returned to Greece aboard of the S.S. Madonna, which departed on February 9, 1923. None of the eleven deportees were from Smyrna; four were Greeks from Tenedos, modern Bozcaada, and one from Kaisareia, modern Kayseri. There were also fifteen Armenians: nine were from Nikomēdeia, modern Ismid, and five from Aintob, modern Gaziantep, Turkey.[5] The remaining thirty-three were deported on various dates and with various ships. Therefore, the seventy Smyrna refugees were not former passengers of the Acropolis. This is an important fact for the reader to keep in mind as the refugees’ story unfolds.

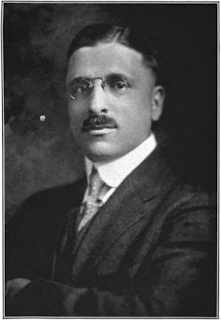

Attorney Malcom Vartan Malcom

A lawyer named Malcom Vartan Malcom was the Smyrna refugees’ primary advocate to the press. He himself being an immigrant from Sivas, Turkey, Malcolm was a champion of Armenian immigrants. He studied at Harvard Law School and graduated in 1913. By 1916 he moved to New York City and resided at 2 Rector Street.[6] In 1919 he authored a book entitled The Armenians in America, and five years later he testified in a case challenging the legal obstacles that Armenians encountered in attaining US citizenship.[7]

Judge Learned Hand

Federal Judge Learned Hand was another Harvard Law School graduate who influenced the fate of the Smyrna refugees. Hand was born in Albany, New York, and graduated from Harvard in 1896.[8] He moved to New York City in December of 1902 and married France Frincke.[9] His wife was a well-known philhellene and undoubtedly impacted Learned’s disposition toward the Smyrna refugees.[10] When they arrived at Ellis Island, Hand was the presiding federal judge in New York City. He granted a writ of habeas corpus to Malcom and thereby a stay of the refugees’ deportation order and a hearing of their case. His action was standard legal procedure but it also challenged the authority of Ellis Island agents.

Two Ellis Island officials played the most crucial role in the Smyrna refugees’ story: Robert E. Todd and Harry R. Landis. Todd was appointed as commissioner of Ellis Island in 1921. Harry R. Landis served as Assistant Commissioner during Todd’s time in office. Both Todd and Landis strictly interpreted the process of deportation. Their actions became the subject of news reports that fomented implications of racism and publicly tarnished the refugee vetting process.

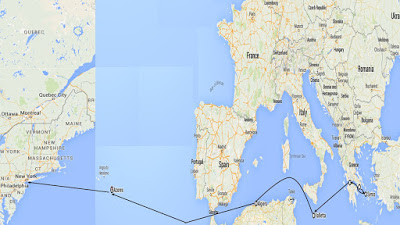

Journey of the SS Acropolis

The journey for the Armenian and Greek refugees was arduous and long, lasting anywhere from two weeks to a month. This trip’s long duration was due to the coal-powered ship engine technology of the time as well as the quarantine hold times of passengers in camps in Constantinople, Piraeus, and Patras. Perhaps one of the worst case scenarios occurred to the Armenian and Greek refugees of the passenger vessel S.S. Acropolis. The ship left Piraeus on November 2, 1922, for the island of Syros. After making port it proceeded for Patras and arrived there on November 10. At Patras two hundred refugees from Constantinople were urged to board. Horace Stiles, the US Consul in Patras, warned the Greek authorities that the immigration quota pertaining to Armenians and Greeks for that year had already expired. The ship spent thirty-four days docked in Patras due to a crew strike and lack of provisions for the journey. Finally, on December 13, the ship set out for Valletta, Malta with seventy of the refugees on board, in addition to three hundred first- and second-class passengers. The fuel was entirely consumed during the journey to Malta and the crew started to burn wood from the ship itself for additional fuel. The Acropolis reached Malta on December 18 and stocked up on coal and provisions. While there the ship’s captain deserted and the ship’s crew continued the journey to New York, making two more mandatory stops for fuel in Algiers and the Azores. During this journey, two babies were born on board.[11]

Four days later the Acropolis reached New York harbor but “Immigration officials refused to permit any of the immigrants to land until the Federal authorities in Washington had ruled on the cases of Greeks, Armenians and others whose quotas have been exhausted.” Upon arrival, seven refugees were hospitalized and one of the seven, Ankino Ashakian, passed away in Ellis Island’s infirmary. The seventy refugees were facing deportation to Piraeus because the Greek officials embarked them despite the consul’s warning.[12]

From an article dated February 9, 1923, we learn more about the refugees’ story.

Ninety Smyrna refugees, mostly Armenians and Greeks, were deported…to Greece. They were sent back by the United States Government because the quotas for Armenians and Greeks…were exhausted for the fiscal year ending 30 June 1923. The majority of those who sailed yesterday were women and children. The Secretary of Labor refused to make any exception in their cases. The deportees will be landed at Piraeus, Greece.

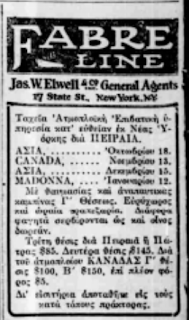

The refugees’ ship was called the Madonna and belonged to the Fabre shipping line.[13] Malcom evoked the literacy exception of the Immigration Act of 1917 for religious refugees in order to acquire a writ of habeas corpus. The writ applied to fifty-one Armenian refugees only. However, the reportage contested the timeliness of the writ’s delivery to Robert E. Todd. According to Todd, the ship was already under way when he received the writ of habeas corpus. Malcom insisted that the writ was served to the commissioner at 5:30 pm, prior to the ship’s departure, and not at 6:00 pm when the ship was already en route.[14] Additionally, an official on the ship offered to stop it and allow the Armenians to disembark but Todd refused.

In Malcom’s own words:

After obtaining the writ of habeas corpus from Judge Hand, which would have enabled these Armenians to obtain consideration as persons persecuted for their religion, which they are, I telephoned to Ellis Island to announce the fact and to arrange to put the men, women and children of[f] the ship. I could not get the Commissioner at first, but talked to a Mr. Landis, who refused to listen to the suggestion that he should confirm the issuance of the writ and take the people off the ship.[15]

Malcom relayed Todd’s statements to the press and thereby provided evidence of Todd’s endorsement of one-hundred percent Americanism.

Malcom relayed Todd’s statements to the press and thereby provided evidence of Todd’s endorsement of one-hundred percent Americanism.

At any rate, when I informed Mr. Landis of the habeas corpus he spoke very angrily, said I was trying to break the law and that he would do nothing for me. It was too late to get over to Ellis Island with the writ, so I went to the Battery with Mr. Jones, an official of the Fabre Line, who had two tugs ready to go down the bay and take off the persons named in the writ…Mr. Tod[d]… came on a late boat. I served the writ on him. He was extremely angry. He said no such writ had ever been served on him before. He said the Armenians were a dirty lot, and that he would do nothing for them. Mr. Tod[d] repeated that they were in excess of quota and that he would not give the authority to do this, writ or no writ.[15]

In the same article, Todd defended his decision and rejected the implications of 100 percent Americanism.

When Mr. Tod[d] was asked … if he received word of the issuance of the writ before the boat sailed, he said: ‘Oh, we can’t pay any attention to telephone communications. We don’t know anything about where they are coming from. The fact of the matter is that the writ was not served until it was too late to act on it.’ The United States District Attorney has ruled that we are not to interfere with ships that have started on their way. If we interfered in this case, the ship would have been held up for hours. How could we know whether we were getting the right ones? In regards to the charge that he referred to the Armenians as ‘a dirty lot’ he replied, ‘I used no such language and said nothing that reflected on them in any way.[15]

The article concludes:

Members of Congress have taken cognizance of the fact that hundreds of thousands of Armenians have been slaughtered by the Turks and bills had passed both houses which were intended specifically to save refugees of this kind from deportation.[15]

It is unclear to which “bills” the news article was referring. As already stated, the Immigration Act of 1917 allowed exemptions from deportation. The reason these refugees could even be considered for an exemption was their classification as religious refugees. Malcom implied that 100 percent Americanism influenced Todd’s judgement but neither party took legal action against the other. The publication of such a charge, however, may have tarnished Todd’s reputation. Although the exact cause is unknown, Henry Curran relieved Todd of his post later that year.[16] The Acropolis’s journey ended with its transfer of the Smyrna refugees to New York. This was the ship’s final voyage by that name. The Borras Shipping Company purchased it at some point prior to April 28, 1923 and renamed it as the SS Washington.[17] The Madonna transported the Smyrna refugees back to Greece on February 9, 1923.

Endnotes

[1] Michael C. LeMay and Elliott Robert Barkan, U.S. Immigration and Naturalization Laws and Issues: A Documentary History, Primary Documents in American History and Contemporary Issues (Westport, CT: Greenwood Press, 1999)., 133.

[2] Ibid, 109.

[3] Ethnikos Kēryx, “Apo tas Zōntanas Tragōdias: 90 Prosfyges Smyrnēs Epistrefontai eis tēn Ellada,” Hellenic Parliament Digital Library. February 10, 1923. http://srv-web1.parliament.gr/display_doc.asp?item=44690&seg= 11791. Accessed December 13, 2015.

[4] I determined this number by taking the sum of all passengers’ names marked for deportation.

[5] Aintob was the spelling in the Ellis Island ship manifest. I assume this is a misspelling of the word Gaziantep made by the Ellis Island ship manifest clerk.

[6] Trow Printing and Booking Company’s 1916 New York City Directory (New York: Trow Printing and Booking Company, 1916), 1118, digital images, Ancestry.com. Accessed December 1, 2015.

[7] “United States V. Cartozian,” ed. Judicial Branch (http://www.leagle.com/decision/19259256F2d9191595/UNITE

D%20v.%20CARTOZIAN:LEAGLE, July27, 1925). Accessed December 5, 2015.

[8] Gerald Gunther, Learned Hand: The Man and the Judge, 1st ed. (New York: Knopf, 1994)., 44.

[9] Ibid, 82.

[10] Ibid, 462.

[11] The Ellis Island Archives verify the birth of one baby girl to Armenian parents off the coast of

Kalamata, Greece. For evidence of the birth, see New York, Ellis Island Foundation. 1892-1924. “The American

Family Immigration History Center’s Ellis Island Archive,” Ellis Island (Online: The Statue of Liberty-Ellis Island

Foundation, Inc., (2009), http://www.ellisislandrecords.org/: accessed 7 September 2015) entry for Acropolis

Levonian, age 1 month, arrived on the Acropolis; citing Passenger Lists, 003 – 1 Jan 1904 to 31 Dec 1924, Image

0176; National Archives, Washington.DC, United States.

[12] New York Times, “Jinx Pursues Ship Here 37 Days Late,” New York Times (1924-Current File), January 17, 1923. http://search.proquest.com/docview/103228070?accountid=10920. Accessed December 15, 2015.

[13] New York Times, “90 Smyrna Refugees Deported to Greece,” New York Time (1924-Current File), February 10, 1923. http://search.proquest.com/docview/103233187?accountid=10920. Accessed December 15, 2015.

[14] Brooklyn Daily Eagle, “Exiled Refugees Not Russian, Face Turk, Malcom Says,” February, 13, 1923. The Brooklyn Daily Eagle (1841-1955). http://bklyn.newspapers.com/search/#lnd=1&query=Exiled+

Refugees+Not+Russian%2C+Face+Turk%2C+Malcom+Says&t=1890. Accessed December 15, 2015.

[15] New York Times, “Refugees Deported in Spite of a Writ,” February 11, 1923. New York Times (1924-Current File), http://search.proquest.com/docview/103225116?accountid=10920 Accessed, December 15, 2015.

[16] August C. Bolino, The Ellis Island Source Book (Washington, DC: Kensington Historical Press, 1985), 94.

[17] New York, Ellis Island Foundation. 1892-1924. “The American Family Immigration History Center’s Ellis Island Archive,” Ellis Island (Online: The Statue of Liberty-Ellis Island Foundation, Inc., 2009), http://www.ellisislandrecords.org/: accessed 5 September 2015) entry Statement of Master of Vessel Prior Regarding Changes in Crew Prior to Departure; citing Passenger Lists, 1 Jan 1904 to 31 Dec 1924, Image 0228; National Archives, Washington DC, United States.

Bibliography

Bolino, August C. The Ellis Island Source Book. Washington, DC: Kensington Historical Press, 1985.

Brooklyn Daily Eagle, “Exiled Refugees Not Russian, Face Turk, Malcom Says,” February, 13,

1923. The Brooklyn Daily Eagle (1841-1955). http://bklyn.newspapers.com/search/

#lnd=1&query=Exiled+Refugees+Not+Russian%2C+Face+Turk%2C+Malcom+Says&t=1890. Accessed December 15, 2015.

Ethnikos Kēryx, 1923. Apo tas Zōntanas Tragōdias: 90 Prosfyges Smyrnēs Epistrefontai eis tēn

Ellada,” Hellenic Parliament Digital Library. February 10. http://srv-web1.parliament.gr/ display_doc.asp?item=44690&seg= 11791. Accessed December 13, 2015.

Gunther, Gerald. Learned Hand: The Man and the Judge. 1st ed. New York: Knopf, 1994.

LeMay, Michael C., and Elliott Robert Barkan. U.S. Immigration and Naturalization Laws and Issues: A Documentary History. Primary Documents in American History and Contemporary Issues. Westport, CT: Greenwood Press, 1999.

New York, Ellis Island Foundation. 1892-1924. “The American Family Immigration History

Center’s Ellis Island Archive,” Ellis Island (Online: The Statue of Liberty-Ellis Island Foundation, Inc., (2009), http://www.ellisislandrecords.org/: accessed 7 September 2015) entry for Acropolis Levonin, age 1 month, arrived on the Acropolis; citing Passenger Lists, 003 – 1 Jan 1904 to 31 Dec 1924, Image 0176; National Archives, Washington.DC, United States.

New York, Ellis Island Foundation. 1892-1924. “The American Family Immigration History

Center’s Ellis Island Archive,” Ellis Island (Online: The Statue of Liberty-Ellis Island Foundation, Inc., 2009), http://www.ellisislandrecords.org/: accessed 5 September 2015) entry Statement of Master of Vessel Prior Regarding Changes in Crew Prior to Departure; citing Passenger Lists, 1 Jan 1904 to 31 Dec 1924, Image 0228; National Archives, Washington DC, United States.

New York Times, 1923. Jinx Pursues Ship Here 37 Days Late, New York Times (1924-Current File), January 17. http://search.proquest.com/docview/103228070?accountid=10920.

Accessed December 15, 2015.

New York Times, 1923. “90 Smyrna Refugees Deported to Greece,” New York Time (1924-

Current file), February 10. http://search.proquest.com/docview/103233187?accountid=1

0920.Accessed December 15, 2015.

New York Times, 1923. “Refugees Deported in Spite of a Writ,” February 11. New York Times

(1924-Current File), http://search.proquest.com/docview/103225116?accountid=10920 Accessed, December 15, 2015.

Trow Printing and Booking Company’s 1916 New York City Directory (New York: Trow

Printing and Booking Company, 1916), 1118, digital images, Ancestry.com. Accessed December 1, 2015.

United States V. Cartozian, ed. Judicial Branch (http://www.leagle.com/decision/19259256F2d

9191595/UNITED%20v.%20CARTOZIAN:LEAGLE, July27, 1925). Accessed ` December 5, 2015.